(Image: MyGalaxies, a site using Sloan Digital Sky Survey galaxies to write messages.)

Writing about science

As a citizen scientist takes part in a project, they become curious about the science behind it, and may do some reading of their own. They may then write about this or ask further questions on your discussion forum, blog or social media. This can not only teach other participants something, but also provide an opportunity for peer-to-peer discussion: others may point out inaccuracies, or ask further questions, and bounce ideas off each other. Of course, there is always a risk that someone will write something incorrect with enough confidence or authority that it will become widely believed, as is the case everywhere. You may find that fact-checking is added to your duties! You may even find out something you did not know.

It is very moving to learn that your project has led to someone learning more, but this is just the beginning. The process of writing for their peers might be a new experience for the volunteer. They may decide to take up serious study of the topic, or go on to do outreach of their own.

The Scientific Method

Richard Proctor’s study of irregular galaxies (which we met in “Community Building”) produced some discussion on the Galaxy Zoo Forum which revealed an understanding of the scientific method by people who were not trained scientists, and may not even have heard of it. A conference poster notes the following sentences written by non-professionals:

These statements showed an appreciation of large sample sizes and for consistency during an experiment, and a knowledge of how to build on existing data. It is an example of “learning by doing”.

Art and Fun

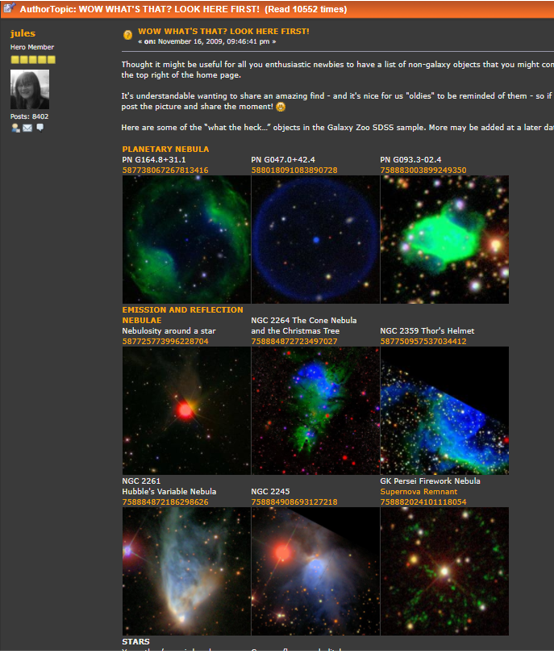

(Image: Galaxy Zoo volunteer Alexandre d'Or sketched a galaxy as an imaginary animal. Credit: Alexandre d'Or, Galaxy Zoo, Sloan Digital Sky Survey.)

Some scientific phenomena (such as astronomy and the natural world) is beautiful and easy for people to use to create art – whether collages of existing images or, as we see here, paper sketches. These are not necessarily serious, but people may put a great deal of effort into them!

A particularly entertaining example was the “Galactic Alphabet” (which inspired the course image for this module). Some galaxies and nebulae were very distorted by gravitational interaction with other objects and looked like letters of the Latin alphabet. A collection on the Galaxy Zoo Forum was made of these, and a spinoff site called “MyGalaxies” was created by a scientist named Stephen Bamford, in which you can write messages in galaxy images (as we see at the top of this page). Bamford and another astronomer went on to write a spoof paper for an April Fool joke. Volunteers can have an effect on professional scientists, too.

Tutorials

Volunteers may write excellent tutorials for each other – often better ones than the project creator, because they understand how other volunteers are thinking and feeling. These tutorials may be technical (“How do I do this?”) or scientific (“I found this, what is it?”). The screenshot we see here is of a tutorial written by Julia Wilkinson for the Galaxy Zoo Forum and is of types of astronomical object that are mostly not galaxies but which volunteers kept finding and asking about. (You can still find it here, but because many of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey images are old, several no longer load.)

Volunteers may also anticipate the needs of newcomers, for example by creating a special thread for welcoming them and allowing them space to practice image posting or data analysis.

When content like this is produced, showcase it! Incorporate it into your regular news posts, both to thank your volunteers and to encourage more newcomers to visit, knowing that they’ll get a great welcome.

News posts and blogging

Small frequent news posts that take place on a website or discussion forum (rather than being e-mailed to people) may be “the reason I visit this site every day, to see what today’s Object of the Day will be”. Producing these can start to take up a great deal of your time, even if your team takes turns – but your volunteers may want to gradually take over the process. It will be a good idea to monitor their work for accuracy, but you may find that they put in an enormous amount of effort. They may highlight a side project they have started, or incorporate the general science they are learning. This may be part of your project’s discussion forum or blog.

If someone’s artwork, or general science reading, or even blog post, is not a direct contribution to the results of your project, this is not a problem! If people are engaged and it’s inspiring them to create something, this is a significant outcome for them. And an online community will fail if it does not create content, no matter how sound the science outcomes of the project.

Activism or engaging the wider community

A volunteer may take up public speaking or writing – for example, they may want to share the delights of astronomy with their community, to teach those around them a skill they have learned, or to raise awareness of or directly tackle an environmental issue. This may recruit more participants for your project, or simply be one of your unexpected (but thrilling) results. Your project, or community, may have been a springboard for them to carry out something new.

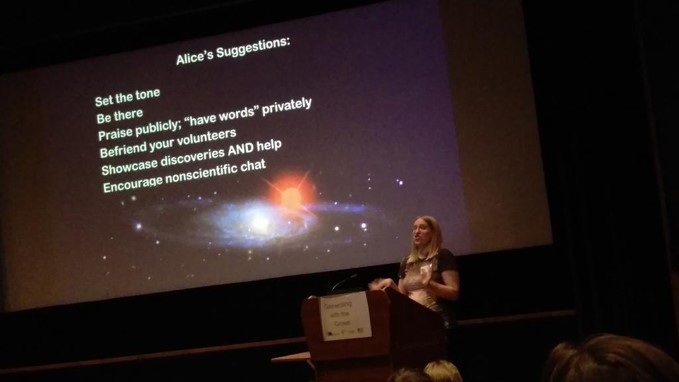

Your volunteers may end up training academic researchers - for example, in community management, as in the case of this course's leader!

(Image: Alice Sheppard giving a talk on online communities. Credit: UCL ExCiteS.)Mentorship and collaboration

Mentorship is still quite rare in citizen science but extremely valuable; Jennifer Preece, a researcher in human-computer interaction, found that “Although volunteer training tended to go hand-in-hand with higher quality data and productivity, not many scientists got involved in training volunteers.” Ideally, researchers would also be able to train volunteers to read and write academic literature, or even study skills to enter and pass academic courses. This is not unknown, but is of course rare due to time constraints.

Citizen scientists have occasionally collaborated directly with a professional. Sharman Apt Russell, for example, worked with professional ecologists to study beetles in the field, about which she wrote the book Diary of a Citizen Scientist: Chasing Tiger Beetles And Other New Ways of Engaging with the World. Zooniverse volunteers who have made significant discoveries or created software used in Zooniverse work have been made authors of scientific papers.

Citizen scientists, of course, may well decide to mentor, train or work with each other. The training is not necessarily one-sided – someone with a background in computing may work with someone else with a high level of subject knowledge, complementing each other’s skills.

Concluding remark

Virtually none of this can take place without a platform for discussion and community. A citizen scientist working alone might decide to write a social media post about their participation in your project; but without input or conversation with other people, their work will receive far less feedback, nor will they necessarily have an encouraging audience to share it with.