We all hear "avoid jargon!", but the longer you’ve been working in research, the more used to it you will be and the harder it may be to avoid it! It may be worth reading some popular science articles on your subject, or writing something and asking someone who works in a completely different sector to tell you, honestly, which parts were unclear.

If a word or concept will come up frequently, however, do include and explain it. For example, Etch-A-Cell opens with "Help us study one of the biggest structures found in your cells - the Endoplasmic Reticulum". It doesn't define endoplasmic reticulum at the time, but rather offers a more detailed explanation with links to other explanatory sites later, when the volunteer is ready. Don't avoid the science! Citizen scientists are fast learners and usually very curious about it.

Here is a tactic to test whether you have explained a word clearly or not. It is from this 1966 speech by Richard Feynman, who had just criticised a school science textbook for introducing the word “energy” but not explaining the concept:

Test it this way: you say, “Without using the new word which you have just learned, try to rephrase what you have just learned in your own language. Without using the word ‘energy’, tell me what you know now about the dog’s motion.” You cannot. So you learned nothing about science …

I think for lesson number one, to learn a mystic formula for answering questions is very bad. The book has some others: “gravity makes it fall”; “the soles of your shoes wear out because of friction.” Shoe leather wears out because it rubs against the sidewalk and the little notches and bumps on the sidewalk grab pieces and pull them off. To simply say it is because of friction is sad, because it’s not science.

A similar problem can occur when a website is written with grandiose or specialist phrases such as “promote a step change”, “empowerment”, “innovative solutions”, “capacity building”, “build on the work of …” These can sound as if you are trying to impress other scientists or grant funders while ignoring the actual citizen scientists, who may read such phrases and retort, “Sure, but what do you actually want me to do?” There’s nothing wrong with sounding ambitious about your aims, especially once people are involved and excited. But start simple and specific, such as “Explore and share your observations from the natural world”.

The best people to tell you if you have explained something in a jargon-free way are your volunteers. You will learn a lot from seeing how they write about your project, if there is a way for them to do this.

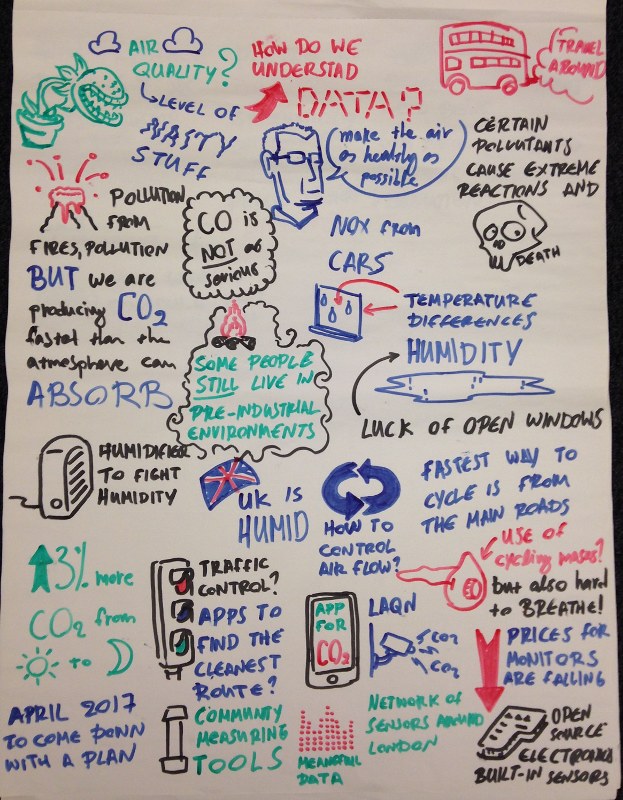

(Image: Doing It Together Science / UCL)