Makerspaces (also called Fab Labs or Hackerspaces) are public workspaces where people can access tools and equipment, meet other people and collaborate with the ultimate goal of making things and learning. While they usually have a focus on building with technology, they also include other types of making and crafts.

Makerspaces are part of maker culture and have a strong DIY ethic. They’re often run as nonprofit organisations. These spaces enable you to do something yourself rather than buying something off the shelf or having somebody do it for you. The social aspect of a makerspace, where people come together to share what they’ve made and help each other learn, is often as important as the facilities they provide.

Many makerspaces started as small communities, but organisations like the Fab Lab network link makerspaces worldwide. Fab Labs sign up to the Fab Lab Charter, which includes a commitment to open access for anybody. It’s also becoming increasingly common to see libraries provide makerspace facilities, which share the ethos of making resources freely available, especially in the United States.

Many makerspaces focus on digital fabrication, especially using 3D printers and laser cutters. These are computer-controlled tools that can fabricate objects based on digital designs, such as 3D models. These tools can be expensive to buy yourself and take up a lot of space. Makerspaces seek funding or donations to make them available to the public at low cost.

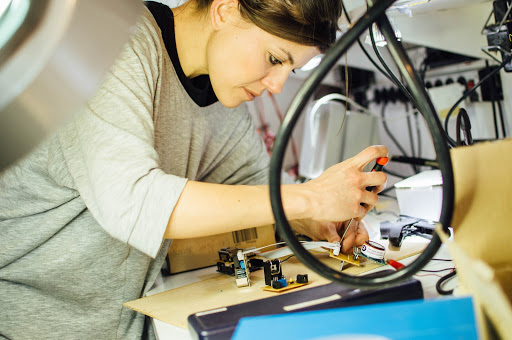

Electronics equipment is another common facility provided at makerspaces. Computer enthusiasts originally started many of these spaces, and members make use of open-source hardware like Raspberry Pi and Arduino, which are designed to be easy for new makers.

Alongside technology-focused facilities, makerspaces often have traditional woodworking tools, and some spaces have begun to branch out into other types of fabrication, including professional sewing machines.

Makerspaces are a great example of people coming together to form a community around a shared interest, bringing a diverse set of skills. They often host workshops around particular technologies or topics, as well as hackathons where lots of people come together to build things quickly over a weekend. There are lots of opportunities for Citizens’ Observatories to harness this energy.

One of the best-known examples of this is Fab Lab Barcelona which was the birthplace of Smart Citizen. They have worked with many different citizen science projects to help citizens to build their own sensors. We’ll learn more about Smart Citizen in the next step.

Many cities now have at least one makerspace, and the best place to find them is online. A good starting point is Make’s online directory, which includes over 800 spaces worldwide.

Makerspaces usually require a membership to gain full access, but many have a designated time each week when they’re open to everyone.

You don’t need expensive or complicated scientific equipment to monitor your environment. There are lots of simple ways to collect data about the world around you; there are also many ways to build your own sensors with a little bit of technical skill. Data collected this way can still be useful to scientists, for campaigning or making better decisions, and for your own interest!

Sensors don’t have to be complicated! For example, if you wanted to learn about rainfall, you might build a simple container to collect rain and measure it every day. But there are also more sophisticated experiments you can run yourself with simple equipment.

Public Lab are a DIY environmental science community who make a variety of toolkits for building simple sensors. Their Foldable Paper Spectrometer turns your smartphone camera into a simple spectrometer—a tool that scientists use to measure different types of light and learn about materials. Some of their other kits use cameras attached to kites and balloons to help citizens map areas from above. Citizens used this method to capture images of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

We can build more sophisticated sensors using some DIY electronics. My Naturewatch has designed a wildlife camera that you can make yourself using a Raspberry Pi Zero (a tiny, dual-display, desktop computer), a USB power bank, and some household objects. Nature Bytes has also designed a build-your-own camera based on the Raspberry Pi A+ and Pi camera, for which they have also designed a 3D-printed case. Set either of these cameras up in your garden, and it will capture photos of birds that you could use to understand patterns of wildlife in your local area.

In previous steps, we heard about Smart Citizen and the sensor toolkit that comes ready-made with sensors including noise, air temperature, light, humidity and air quality. The toolkit connects to an online platform to share data. If you have a little more experience with coding, you can even extend it to build your own sensors and experiments.

Once we know how to build some sensors and collect data, what can we use them for? Making Sense was an EU-funded project that used the Smart Citizen kit to help people collect data on noise and take action together. They worked with communities to understand what local issues mattered to them, design sensors and experiments. The data collected by participants were used as evidence to campaign for changes.

In a previous video we spoke about one of their projects centred around noise pollution in Barcelona, where residents were often kept awake by crowds of people sitting on the local square. They used Smart Citizen to build a public installation to show noise levels and help people reflect on noise levels. In Kosovo, the Making Sense team collected data about air quality that led to a ban on cars and a change to the country’s constitution to demand the right to clean air!

In this video, you heard from Dahlia Domain of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Austria. Crowdsourcing data is a phenomenon that has grown over the last decade. In crowdsourcing projects, citizens contribute data for a specific task that could otherwise not be collected with existing resources.

Dahlia showed you some different kinds of crowdsourcing applications. You can use some of these from the comfort of your home using just your computer or mobile device. Others require you to go outside and collect land-related data in the field using your smartphone.

Dahlia talked about Geo-Wiki, a crowdsourcing tool used for the collection of land cover data. Citizens are asked to look at high-resolution satellite images and identify different features of the landscape. The data collected have been used in various land cover mapping applications.

FotoQuest Go and CityOases are mobile apps for crowdsourcing land-related data in the field. These data can provide information that can be used by planners, decision-makers and researchers.

You can find examples of past crowdsourcing campaigns on the LandSense Engagement Platform, where you can also get open access to the data. These crowdsourced data can be used in different ways, such as input data for algorithms that classify land cover from satellite images. These algorithms need lots of information about land cover and land use at locations around the world.

In the next step, you will develop your own strategy for data collection. Before you do that, try out at least one crowdsourcing application so you can get a feel for what’s involved. Here are a few options for you to try, select at least one and post a comment to answer the questions below:

1. Download a nature observations app such as iNaturalist or iSpot, and share some observations of nature where you live.

2. Go to the LandSense Engagement Platform and look for an ongoing Picture Pile campaign. Picture Pile is a mobile and web-based app for the rapid assessment of imagery (satellite or photographs). Load the application and swipe away, helping us to classify imagery around different themes!

3. Go to the Zooniverse website and find a campaign that interests you. Make some contributions.

Image 1: Kristian Bang (CC)

Image 2: Making Sense project (CC-By SA)