Let’s start by watching this introductory video on ‘What is Citizen Science?’ produced by the educational organisation Eco Sapien (5 minutes)

Examples of some well-known citizen science projects include:

The UK Royal Society for the Protection of Birds’ Big Garden Birdwatch. Held every January for the last four years, it is now one of the largest garden wildlife citizen science projects in the world in which participants record the birds they see in their gardens over the course of one hour. In the last four years, approximately 500,000 have contributed nearly 9 million hours of monitoring time.

iNaturalist. One of the world’s most popular nature apps, iNaturalist helps you identify the plants and animals around you. It allows you to get connected with a community of over a million scientists and naturalists who can help you learn more about nature! What’s more, by recording and sharing your observations, you’ll create research quality data for scientists working to better understand and protect nature. iNaturalist is a joint initiative by the California Academy of Sciences and the National Geographic Society.

Foldit. Foldit is an online puzzle video game about protein folding. It is part of an experimental research project developed by the University of Washington, Center for Game Science, in collaboration with the UW Department of Biochemistry. The objective of Foldit is to fold the structures of selected proteins as perfectly as possible, using tools provided in the game. The highest scoring solutions are analyzed by researchers, who determine whether or not there is a native structural configuration (native state) that can be applied to relevant proteins in the real world. Scientists can then use these solutions to target and eradicate diseases and create biological innovations. A 2010 paper in the science journal Nature credited Foldit's 57,000 players with providing useful results that matched or outperformed algorithmically computed solutions.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a typology is:

“The study of classes with common characteristics; classification, especially of human products, behaviour, characteristics, etc., according to type; the comparative analysis of structural or other characteristics; a classification or analysis of this kind.”

Typology is a way to look at an area of human activity and group it into specific areas, with suitable labels, so we can talk about them and agree on what it is that we’re talking about.

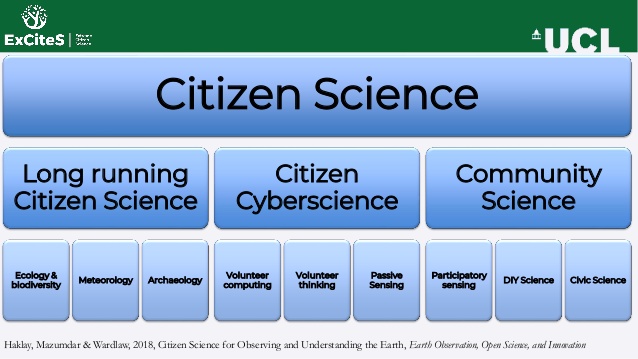

One of the ways in which we can classify citizen science projects is by the length of time they’ve been running (Long-running Citizen Science), high reliance on technology (Citizen Cyberscience), and the relationship between scientists and volunteers (Community Science) (see the figure below).

While the above approach for classifying activities can be used as a way to introduce citizen science, it’s not a great typology as there are many overlaps. Once you start looking at all activities, it is obvious that activities are very broad in terms of:

Projects can include one participant dedicated to chasing tiger beetles to something that millions participate in, and projects can yield a community report or a scientific paper in a top academic journal. How do you capture all of that in one classification?

In addition, we need to consider the ways in which each project is trying to achieve multiple goals not all of them at once, but in each project, some of them are appearing at the same time. Goals such as awareness of the scientific issue of the project, production of scientific knowledge and outputs, concerns over the sampling methodology or the geographical and temporal coverage. Projects also want to be inclusive, increase scientific literacy, find ways to access people's resources (e.g. time) and create an enjoyable and engaging experience. Balancing all these between these different goals is difficult, and the result is that we have a wider range of projects to look at. So making sense of the field is very important.

The result of this complexity is that there are many possible typologies and classifications and if you want to develop one, there are still open aspects to explore. In a review in 2020, at least 13 typologies of citizen science were identified. We will see that the ones that are out there are not perfect and can benefit from further work.

In the next three sections, we will look at typologies that consider the environment of the project, technology, engagement and relationship with professional science:

Haklay (2013) typology